How to talk innovation like a pro

Recent posts

From Firefighting to Innovating: 4 Strategies to Carve Out Space for Creativity

Zoe Aitken • 29 August 2024

COORDINARE’s Four-Day Week Success: 3 Powerful Lessons You Need to Know

Charlotte Rush • 29 August 2024

Everything I thought I knew about Work was Wrong: My Eye-Opening CEO Journey

Tina McIntosh • 1 August 2024

If you have ever sat in on a meeting about innovation, chances are you probably heard a lot of jargon and buzzwords being thrown around. If you want to talk buzzwords with the best of them, use this article as a cheat sheet to help you out.

Alternatively, if you find the buzzwords boring, take this article with you to your next meeting to play innovation bingo. Cross off every term as soon as you hear it – you win if you get all 11.

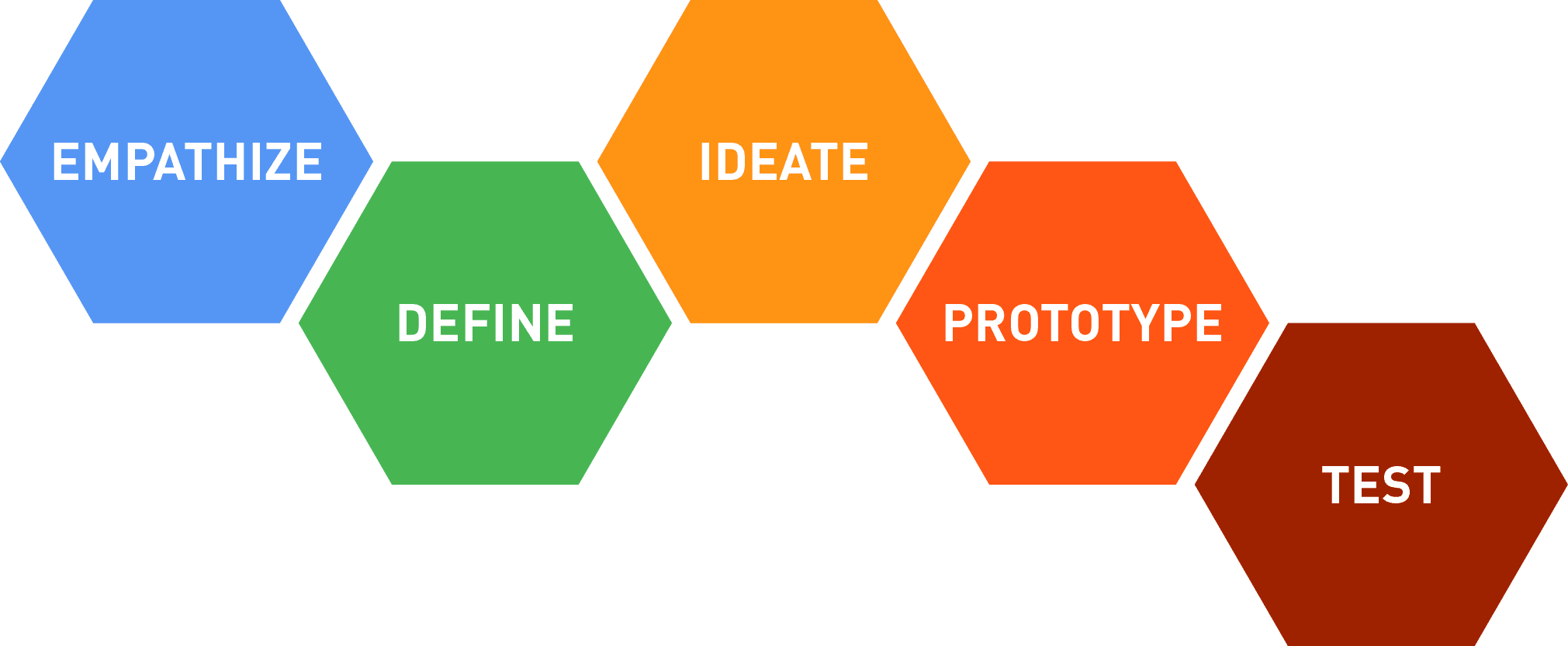

Design Thinking.

Let’s start with one of the biggest buzzwords of them all. For some, Design Thinking is used interchangeably with Innovation, but really, it’s just one of many methodologies on how to innovate.

Design Thinking is based on the process that “strategic designers” (such as those working at IDEO) have been using for many years. It lets mere mortals like us pretend we, too, are talented designers.

Design Thinking is essentially a series of tools that you can use to arrive at an idea that can (hopefully) be implemented. You start by gathering inspiration from customers, use that inspiration to generate creative solutions, and build prototypes to learn how to make your idea better. Having empathy for the customer is at the core of the process, and ultimately the aim is to arrive at a solution that is desirable to customers, feasible to build, and economically viable to create.

A challenge with Design Thinking is that leaders sometimes see it as a panacea for innovation. However, in addition to this methodology, leaders need to consider the organisation’s culture that will support or hinder the success of the methodology, how to motivate individuals to participate in innovation, and determine your innovation strategy in the first place – that is, where you want to focus your innovation efforts.

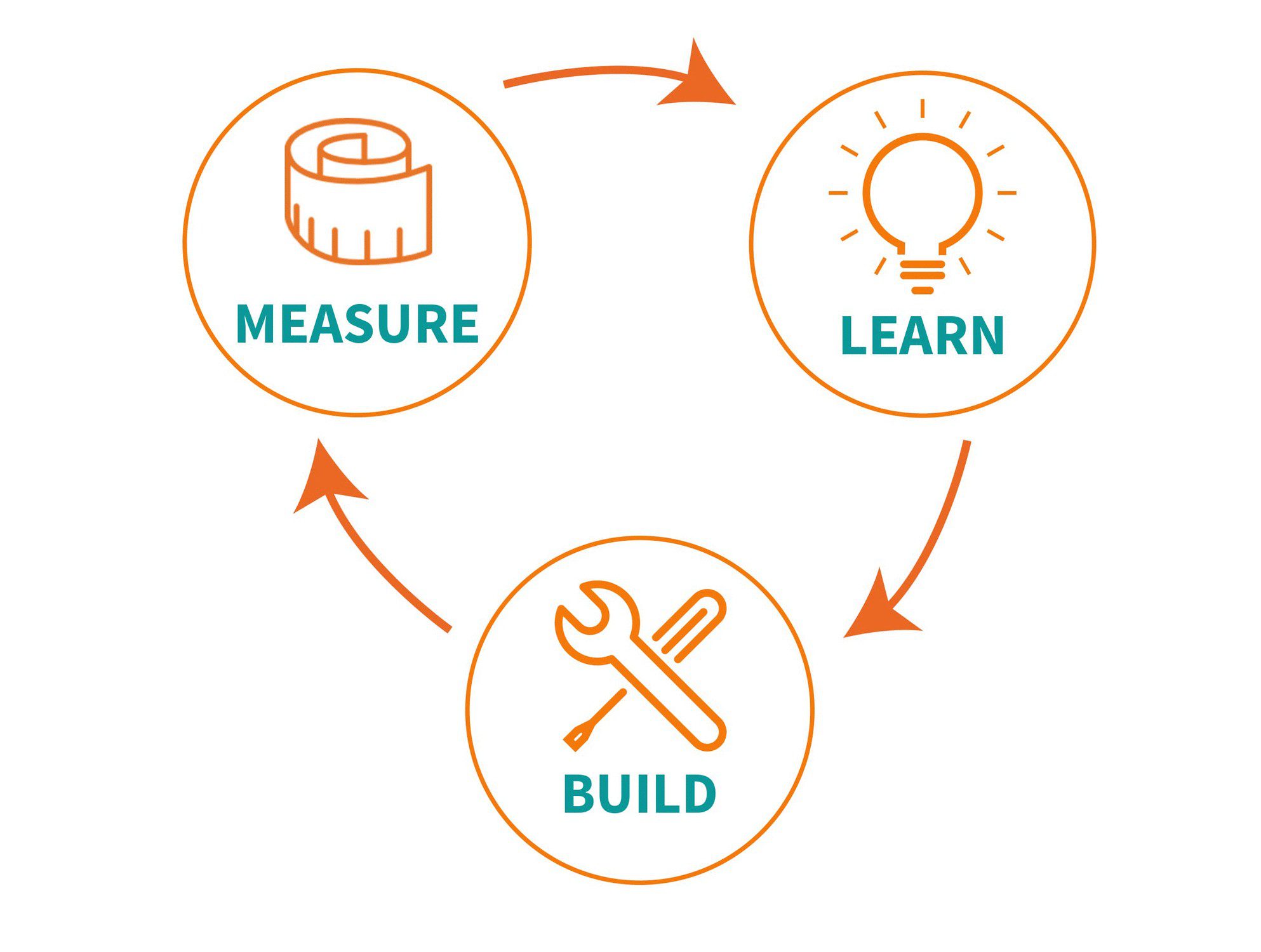

Lean Startup Methodology (LSM).

The easiest way to think of LSM is scientific method applied to business innovation. It involves building a product or service in as little time and money as possible and testing the idea with customers. It contains all the hallmarks of a science experiment: setting hypotheses, designing experiments that show cause and effect, and iterating your idea based on your findings.

Eric Reis, the entrepreneur largely credited with LSM, has done a great job of popularising this approach. Terms such as Minimum Viable Product (the most basic version of an idea that you can build that allows you to test your hypothesis) and Pivot (making a significant change in direction for your innovation) have become part of the vocabulary of almost every start-up founder.

Take note that LSM is most helpful when you actually have an idea that you want to test. Other approaches need to be used to get you to this point in the innovation process.

Lean.

Not to be confused with LSM, is a methodology that was pioneered by Toyota in the 1980s. At its purest, Lean is a system applied to manufacturing processes to remove waste and have things run as quickly, cheaply, and simply as possible.

Since its origins in Toyota’s manufacturing process, Lean has been applied to all sorts of industries, from Government, to banking, and to healthcare. Lean can be great for improving your organisation’s processes, but perhaps don’t rely on it to produce your next big breakthrough idea.

Disruptive Innovation.

Disruptive Innovation is one of the most misused terms in innovation circles. The term comes from research by Harvard Professor and innovation guru Clayton Christensen.

People mistakenly think that for something to be disruptive, it just needs to be big and create lots of road kill. However, the reason why disruptive innovation is so disruptive is because it actually starts off small and in the periphery. This is because disruptors enter at the bottom of a market, often with a seemingly inferior product targeted at the incumbent’s least profitable customers. The disruptor’s offering tends to be one that the incumbent would dismiss as low quality.

As such, the incumbent often pays little to no attention to this new entrant. And this is the very reason why disruptors are so disruptive – the incumbent didn’t see them as a threat.

Over time, the disruptor starts to gain traction and by the time it has gained considerable market share, it is often too late for the incumbent to respond. And hence, it is disrupted. Examples of disruptive innovation in play include what mobile did to fixed line telephones, and what smart phones did to digital cameras.

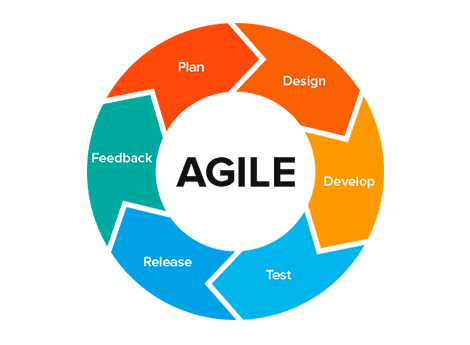

Agile.

I recently had dinner with a friend of mine who heads up transformation for one of Australia’s most successful tech start-ups. We were talking about Agile and she said, “Agile is really just common sense. You communicate, collaborate, move quickly, and iterate based on what you learn.”

That pretty much sums it up.

Agile is a methodology for project management. It typically involves stand up morning meetings, known as Daily Stand-ups, in which people share what they are doing to “sync-up” with each other.

Teams often apply the Scrum framework, in which teams work in short bursts called sprints. Kanban is another popular Agile framework, in which a Kanban board visualises workflow and enhances transparency of where a project is at. A basic Kanban board has three columns: To do, In Progress, and Done.

Agile is great for general principles to follow but it doesn’t replace having a well thought through innovation strategy to direct where you place your agile efforts.

Micro-funding (AKA seed funding).

Micro-funding was pioneered by Y Combinator, one of Silicon Valley’s most famous and successful incubators. Y Combinator famously used to give start-ups an average of $18,000 to build and test their idea. This was in stark contrast to the Venture Capital firms that would often sink $1 million into an idea, if not a lot more.

Y Combinator’s seed funding approach was considered revolutionary at the time, and has paid off in spades. Twelve years after being founded, it’s portfolio is estimated to be worth $80 billion.

Applied to corporate innovation, micro-funding means giving small amounts of money to run innovation experiments. It’s one of the most effective ways to resource innovation, as placing small bets on many projects diversifies risk and limits exposure.

Hackathon.

Hackathons were invented over a decade ago over at Yahoo. Since their incarnation, every man and his dog seem to run them – to huge amounts of fanfare, but to varying degrees of success.

The original intent of a Hackathon was to get a group of smart people together in a room working solo or in small groups to solve problems and build prototypes, which would be showcased at the end of the Hack. Hackathons typically last for a day, although some companies such as Etsy have been known to run ones that last for an entire week.

While Hackathons can be a great way of getting some quick ideas and prototypes, you’ll get more out of it if you have some clear challenges you want people solving. It also helps if you give people training in how to build prototypes or Minimum Viable Products.

One other piece of advice: a Hackathon run in isolation of any other efforts to create a sustainable approach to innovation will more likely do more harm than good. Hackathons do typically create a lot of excitement, but if there is no follow through, you are heading for a big dip in innovation engagement.

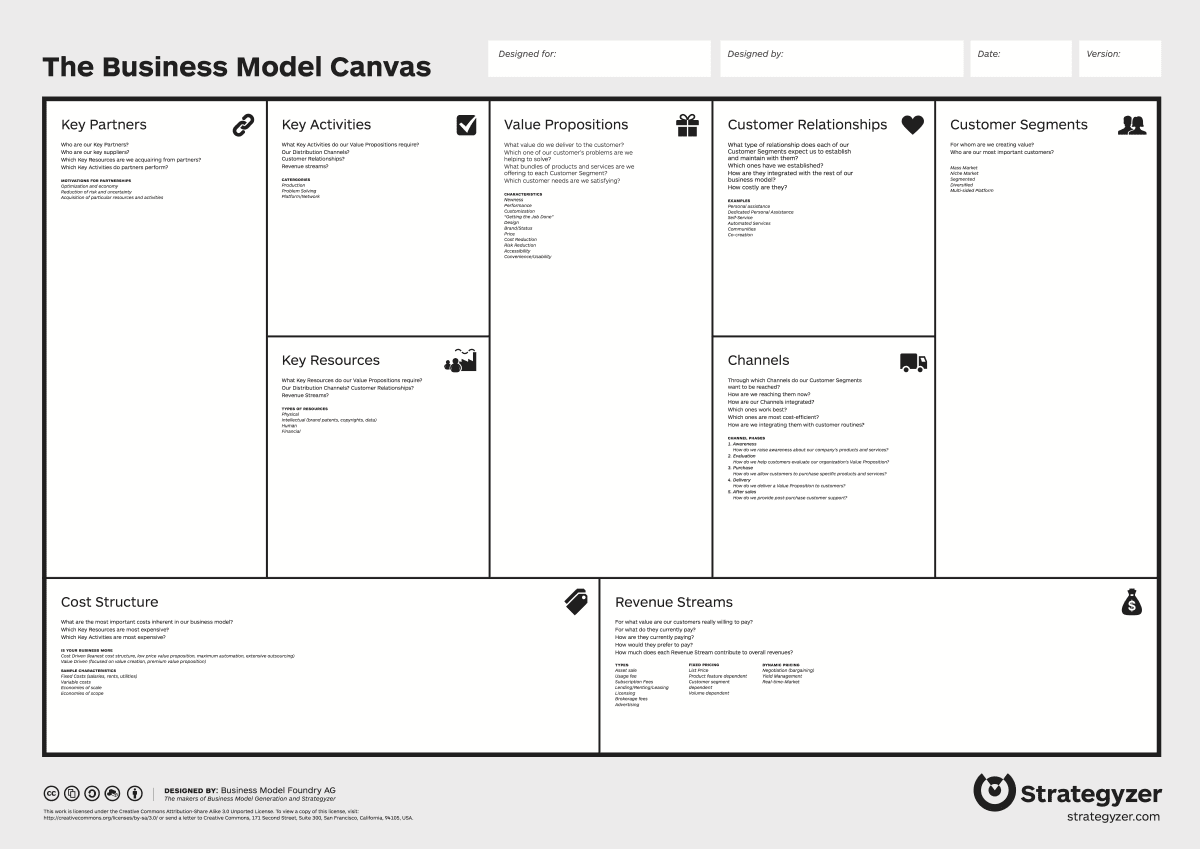

Business Model Canvas.

The Business Model Canvas is a template designed to help flesh out the business model behind an idea. It’s a handy tool for thinking more deeply about an idea – but it’s only useful if you actually have an idea in the first place!

Human-Centred Design.

Refer to Design Thinking. Same thing, different name.

Three Horizons.

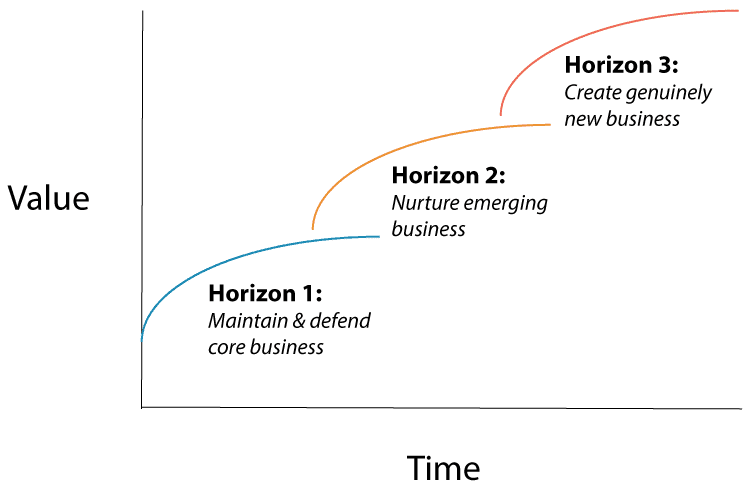

The Three Horizons Framework, developed by Mehrdad Baghai, Steve Coley, and David White from McKinsey, is a framework that helps companies balance their thinking between the core and new future opportunities.

Horizon 1 is all about defending and maintaining one’s core business. Goals in this horizon are typically about maximising margins, driving (immediate) revenue, and improving processes.

Horizon 2 focuses on taking existing products and services and expanding into new markets or launching new, related product lines.

Horizon 3 relates to creating business opportunities that don’t exist today. Typically, Horizon 3 projects are those that will (hopefully) generate significant new streams of revenue in the future. These projects are your big bets, several of which will never actually pay off, but that all companies need to focus on to protect the future of their business.

Unfortunately, many companies only play in Horizon 1 – clearly, this is not recommended. You’re pretty much asking to be disrupted.

Finally, don’t be mislead by graphs of the three horizons that imply the horizons are sequential – to be applied properly, they must all be focused on concurrently.

Science-based Innovation.

As distinct from some of the above methodologies that are from all kinds of sources, experiences and view points, Science-based innovation involves the application of findings from peer-reviewed journals from fields such as organisational psychology, neuroscience, cognitive science and management science.

Because of the mammoth amounts of research to draw on, it provides a holistic view on not only how create a successful innovation, but to build the structure and environment around those skills to ensure innovation flourishes within an organisation.

Science-based innovation resists approaches where there is no evidence or research to suggest that the methodology works. It draws from research studies that go across many industries to ensure the broad applicability of its methods.

While a science-based approach works a treat with cynical groups or so called “left-brained” folk, it may be seen as less useful with companies where innovation is already truly a part of the company’s DNA.

How to decide on the best approach for your organisation

When deciding which approach will be best suited for your organisation, think about innovation as a polygamous relationship. Many companies are loyal to four or five, or even more, of the above approaches.

In deciding which approaches to form relationships with, consider what it is you are trying to solve. For example, is your organisation flooded with ideas, but poor at making the transition to execution? LSM might be a good approach to try. Do teams in your organisation move slowly and without crystal clear focus and transparency? Get some Agile going. Need to create an innovation culture? Science-based innovation provides an evidence-based approach to doing just that.

So don’t feel like you need to commit yourself to just one of the above. Take what serves you, and leave the rest behind.

You are now hopefully feeling like an innovation guru. And if not, hopefully you won your bingo game.

Are you still reading? Want to become a better innovator?

I’ve created a report that explains the six innovation mistakes almost every organisation makes.